Regardless of the route you take, Svolvær on the Lofoten Islands is a seven-hour ride and over 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle Center on the E6, Norway’s main north-south highway. Just getting there is an adventure; it is well inside 66 degrees 33 minutes North.

In early March 2020 I travelled with my eldest son by train from Oslo to Bodø and then took a short flight onto the islands for a photography expedition. The Lofotens remained under a blanket of snow and ice, but the sun was making its return. The timing was critical, even more so than we imagined – two days after we arrived home, Norway went into lockdown. Ever since I have been plotting my return.

The Lofoten landscape is one of the most spectacular in the world, whether covered in snow or bathed in crystal-clear summer light; it gets under your skin. Northwest from Svolvær is the island of Gimsøya, its ancient church, Hoven’s lone peak and, in early March, ice encrusted sandy beaches.

A single-track road circles the northern reaches of this small island where, a few hundred yards back from the beach at Hov, there is a grey, stretched out, low line building in the shadow of Hoven’s 368-meter-tall peak. Facing out to sea, three signs in large arial font declare this is Lofoten Links. Covered in snow, indiscernible from the surrounding farmland, I knew immediately, this was one Golf in the Wild course I was destined and determined to play.

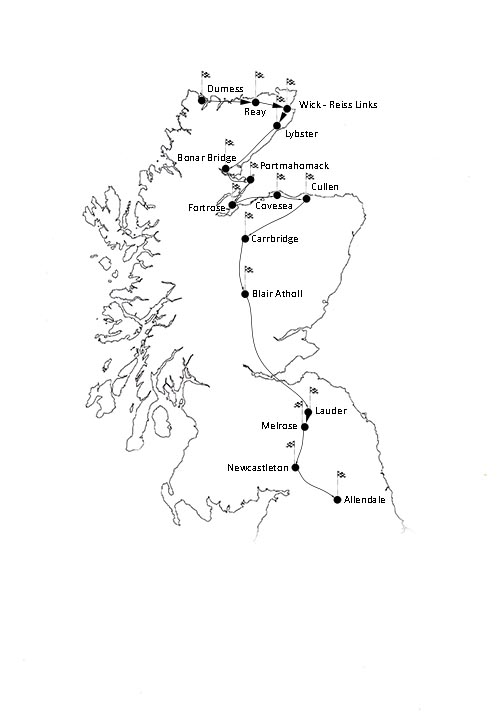

I have travelled Norway by aeroplane, ship, car, coach and train. Returning by motorcycle was the next logical thing to do – if you want to immerse yourself in a landscape over long distance, there is no better way to travel. On Tuesday 27th June 2023, I rode my BMW R1250 GS into the Lofoten Links car park having ridden 1,645 miles and many hours on ferries.

The clubhouse looks to be modelled on up-market Portakabins with potential for extension and I wonder if this might be its history – extended in parallel with the course which has grown from six, to nine, to eighteen holes since 1998. Realised from the germ of an idea first muted in 1991, the course is now included in a variety of top 100 world rankings, including Golf Digest and Golf World – a remarkable achievement.

The golfing season on Gimsøya is cut short by frost and snow which arrives in October and remains until the following Spring. The compensation is that in June and July, the midnight sun enables tees to be booked throughout the night. It is, by some margin, the most expensive round of golf I have played and a far cry from the honesty boxes of Golf in the Wild – the hired clubs are also in a different class from the mixed set of antiques I hired on Barra. Everything is pristine.

The first tee is across the road from the clubhouse where a gravel path leads you through rocky outcrops and a carpet of wildflowers to a choice of tee positions – tee 61 (6092 m), tee 56 (5499 m), tee 48 (4804 m) and tee 42 (4216 m). I was there to enjoy myself, not receive punishment, the ageing joints providing challenge enough – I elected to use tee 48 and avoid some challenging long carries over water. I know my limitations. I know I am not Viktor Hovland, who in 2022, drove 22 hours from Oslo to shoot an 8-under course record of 63. At least I “drove” further.

The first and second holes are the perfect introduction, providing the template for everything that lies ahead, not least because Lofoten Links proudly claims the first to be one of the most challenging opening holes in golf. Standing on the first tee, it is hard to disagree.

This is the view from the 56 and 48 tees, I never looked for the 61 tee, preferring not to dream the impossible dream, nor fight the unbeatable foe. The fairway arcs around the rock-strewn inlet and a narrow band of semi where more boulders await. There is no hiding place, so I played it safe, took a mid-iron to find the fairway and proceeded in a gentlemanly fashion towards the green – I took six. For a golf course that spends half its life buried under snow and ice, the presentation is remarkable with fairways like greens, it seemed a travesty to use a trolley.

The signature hole comes early in the round – the second, Arholmen, ranked one of the best par threes in the world. Again, there is no hiding place, as this image from UK Golf Guy illustrates. I neglected to extract my camera; I was distracted.

This is golfing heaven, but in Norway you can also go to Hell, population 1,528. I have written elsewhere about the surprising parallels between the art of hitting a golf ball and riding a motorcycle. I have found more – we like space in front and behind. On this road trip I discovered another type of hell.

Norwegians are master tunnel builders and monuments to their artistry can be found countrywide, even in the remotest locations. To achieve the greatest undersea descent in the shortest distance, they are steep, spiral and extremely cold. On a motorcycle you do not want to be sandwiched between a campervan driving well below the speed limit and an articulated lorry intent on reading the small print on your rear number plate (for the benefit of the lorry driver – golfinthewild.co.uk). On a golf course you do not want to be sandwiched between a rank amateur in front and enthusiastic long hitters to your rear, you want space.

It was at the second I encountered a dejected girl and her misguided partner. She probably had good reason to be miserable, it being patently obvious that she could neither hit a golf ball nor had any idea of golf etiquette, oblivious as she took an age to clear the green while the world patiently waited. I eventually played out the second and they were still there as I approached the third tee. Her embarrassed partner was good enough to let me through which perfected an already magnificent day. From then on, they provided a very effective buffer for the enthusiastic long hitters behind. I had the fairways to myself. Underground, overtaking the campervan proved more fraught.

I hear the ancient footsteps like the motion of the sea

Sometimes I turn, there’s someone there, other times it’s only me

I am hanging in the balance of a perfect finished plan

Like every sparrow falling, like every grain of sand

Every Grain of Sand – Bob Dylan

Nearby Hov is one of the oldest places in Lofoten and once hosted a huge Viking amphitheatre, probably created for sacrificial rituals – harsh punishment for an over-par round. The Viking chieftan , Tore Hjort, mentioned in the Viking sagas, is thought to have resided here and there are various Viking graves in the area, including two on Lofoten Links. It seems the Vikings had a good eye for inviting links land. The far away course at Reay, on Scotland’s most northerly coast boasts the same – the aptly named Viking Grave, par 3 15th,

I have developed a habit of scoring badly on the front nine and recovering on the back and this day was no different. After 1600+ miles in the saddle, it took time to adjust to walking pace and the coordination required to hit a golf ball rather than balancing clutch, brakes, and accelerator. I expected this and declined the offer of joining Peter and John at the first. This was one day I didn’t want the pressure of an audience. Peter was visiting from Oslo and his friend, John, is a headmaster from nearby Henningsvær, famous for its island football pitch, “the most beautiful football stadium in the world“. Their excellent, controlled drives suggested this was the right decision.

My equilibrium returned at the 8th and I started scoring well from the 10th such that I had the confidence to join them on the last two holes. Coming up short at the par 3, 17th, Peter suggested I was working in yards not metres and he may have had a point. A chip and I was still ten feet short, but the long putt dropped, thereby achieving a reputation as a reliable putter – this reputation is confined to Norway. John lost a ball at the 18th and I had to take a drop from the rough but none of this mattered. Lofoten Links combined with perfect weather had exceeded all expectations. Eventually my golf had risen to the occasion, but again, this was of little consequence – the real achievement was, after months of planning and countless hours on a motorcycle, I had achieved my ambition, playing on the most beautiful golf course in the world. Not so much Golf in the Wild as Golf in Paradise.

The eighteenth is always tinged with disappointment; the round is over and but for the clubhouse chatter, it is time to head for home. This time, home was over 1600 miles and many ferry rides away and given the magnificence of Norway’s landscape, there was much to look forward to. The next morning dawned dull and damp, as if to emphasise just how lucky I had been. An early start to catch the Moskenes – Bodø ferry is why I abandoned the plan to play under a midnight sun. Just now and then, Captain Sensible wins out. The ride south proved as spectacular as the ride north; it is a country that spoils you for anywhere else. There were no dramas on the return leg other than riding through Germany and the Netherlands under a severe weather warning. Safely home, given the opportunity, I would go back tomorrow.