Chapter 9: In the early summer of 1914, Lieutenant Fred Ricketts, a member of the 2nd Battalion of the Argylls, and its army band were stationed at Fort George. An occasional golfer, Fred was playing Ardersier one bright morning when a sharp two-note whistle rang out across the course, swiftly followed by a wayward golf ball. The tuneful hacker had whistled B flat and G instead of shouting “Fore!”. According to Fred’s wife Annie, writing in 1958, the two-note warning with impish spontaneity was answered by my husband with the next few notes. There was little sauntering—Moray Firth’s stiff breezes encouraged a good crisp stride. These little scraps of whistling appeared to ‘catch on’ with the golfers, and from that beginning, the ‘Quick March’ was built up. Frederick Joseph Ricketts was better known by his publishing name, Kenneth J. Alford, the renowned composer of marching-band music. The short refrain that began on the banks of the Moray Firth in the days immediately preceding the Great War would become one of the most instantly recognisable pieces of band music ever written—the appropriately named ‘Colonel Bogey March’. The connection with the golf scoring term is not coincidental.

Tag Archives: Covesea

Golf Mates at Covesea

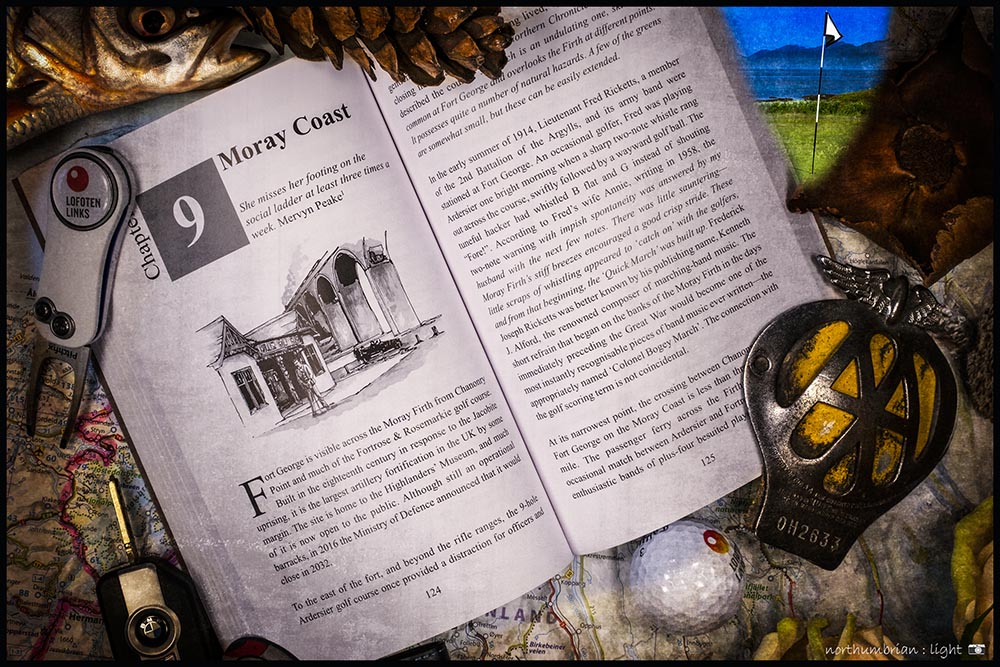

The Golf Mates have discovered Covesea! This entertaining video captures the essence of Andy Burnett’s course in a way that the written word never can. It is the perfect companion to Chapter 9 of Golf in the Wild – Going Home – the Moray Coast:

Built around natural features, high ground, cliff faces, enormous rocks and ideal links land, it is remarkable. Andy Burnett bought the land about fifteen years ago and, with his brother Graeme, expended huge effort in turning it into a 9-hole golf course. … as soon as I saw the place, I fell in love with it completely. Unusually, Covesea is not a members’ club, so the course is entirely Andy’s domain, thereby avoiding the plague of the grumpy golfer who will seek to blame all his misfortune on anything but his inadequate game. Consequently, the usual rules, regulations and members’ priority are entirely missing. “We’ve always run the place without any airs and graces—everyone is welcome to come and play.” It is an operational model that I find extremely attractive.

The heroic trio came to the same conclusions – a remarkable course that golfers must be encouraged to visit – they will not be disappointed.

Golf Club Atlas

I was delighted to contribute to the latest article on Golf Club Atlas – a tour of some of the more quirky golf courses in Scotland and Ireland – Roads less Travelled:

The Route Home

The route for the first book determined itself. The 9-hole courses on the Scottish northwest coast are limited so, it was a simple task of joining the dots from Lochcarron, northwards to Durness. Returning south, beyond Perth, has been an altogether different proposition, there were simply so many choices. In the end, it came down to expediency – I have been lingering in the north for too long and I need to get home. There are fine 9-hole courses in the Scottish Borders I have played for years so, it seemed logical to return via familiar roads. I then realised there was a direct connection between my final destinations and roads didn’t enter into it – the Lauder Light Railway, North British Railway, the Border Counties Railway and the Hexham & Allendale Branch Line. I simply needed to board an imaginary train and I would be home, where ‘home’ is the old Allendale course at Thornley Gate.

Golf in the Wild – Going Home will visit the following courses, with many a diversion along the way: Reay, Wick/Reiss Links, Lybster, Bonar Bridge, Portmahomack, Castlecraig (closed), Fortrose & Rosemarkie, Covesea, Cullen, Rothes, Blair Atholl, Lauder, Melrose, Newcastleton and Allendale (Thornley Gate).

The eagle-eyed will spot a few 18-hole courses among this selection. In the case of the far north, this is simply because there are no 9-hole courses to play – and anyway, Reay and Reiss Links are suitably wild and simply superb.

The old course at Thornley Gate was only a half mile walk from the station, a good deal closer than the centre of Allendale after which the station was named (Catton would be more appropriate). This was a problem repeated along many stretches of these old lines – stations sited too far from the communities they served. When bus services were introduced, rail passenger numbers inevitably went into steep decline.